A simple way to help reduce the pace of climate change!

Image credits: author supplied

Landscape architects are well aware of many factors which are leading to an acceleration of climate change and the associated impacts of this change. Professional activities provide an opportunity to help reduce the climate burden of some of these factors, in sophisticted design interventions, careful specification of materials or choice of processes, defining areas of permanent plant communities or minimising boundary transfers of material, energy or water. Personal choices such as lower energy travel options can also have an influence on our level of contribution to the changing climate.

What may be less well known is the impact of other factors such as dietary preferences; the production of some foods makes a greater contribution to climate change than other foods, and so through thoughtful decisions about diet we can also limit the ways that our food choices will impact on the environment. Moving to a plant-based diet for example, wholly or partially, can have an immediate effect on individual environmental footprints, as well as reducing concerns about some animal husbandry practices, and enabling associated health benefits…

The term ‘whole-food plant-based’ (WFPB) is often used to describe such a diet, rather than ‘vegan’, since it more accurately describes the types of food that have the least environmental impact (soft drinks and potato chips are vegan…). Some vegan foods, particularly those which attempt to emulate animal-based products, fall into the category of being ultra-processed foods (UPFs), with health (and energy) disbenefits first noted in a 2009 paper(1).

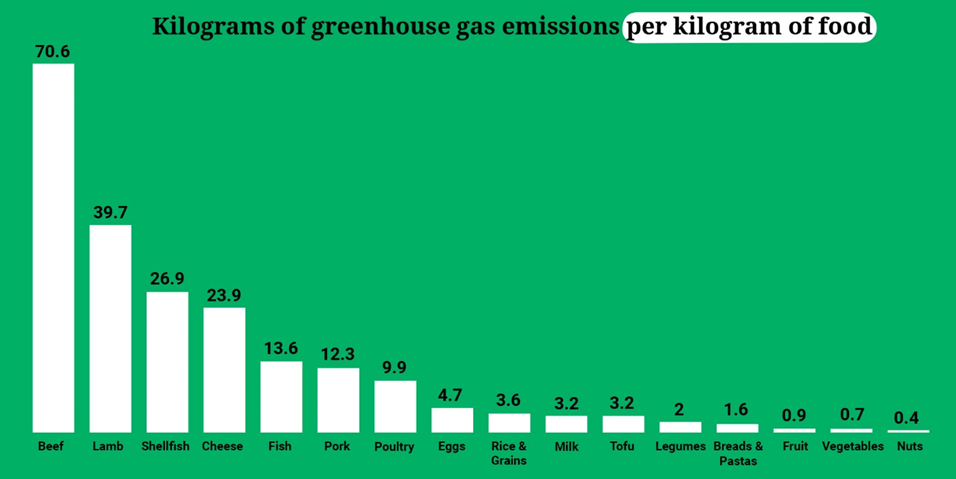

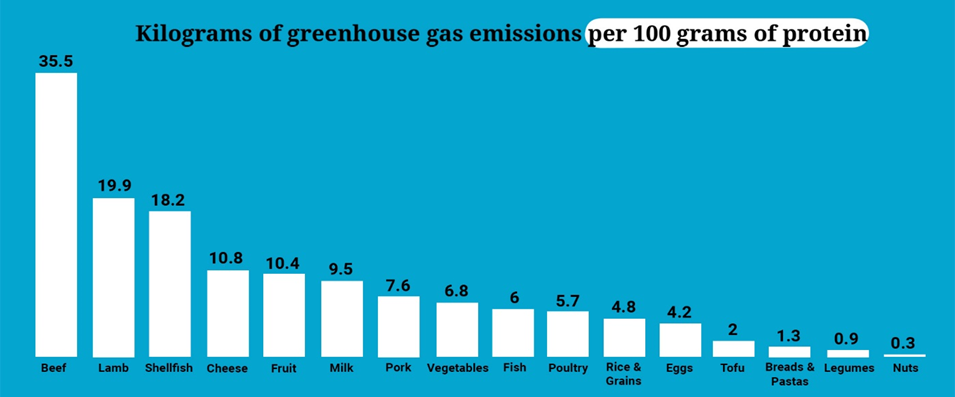

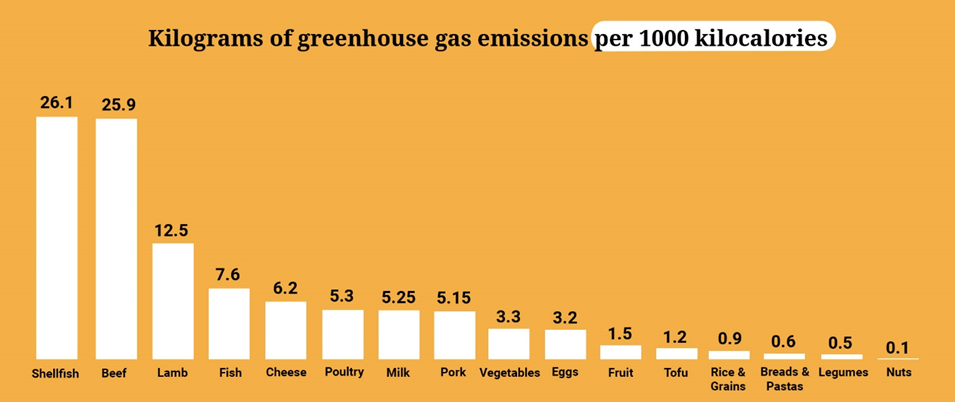

The following three charts published by the UN(2) summarise the key climate-related characteristics of a range of foods:

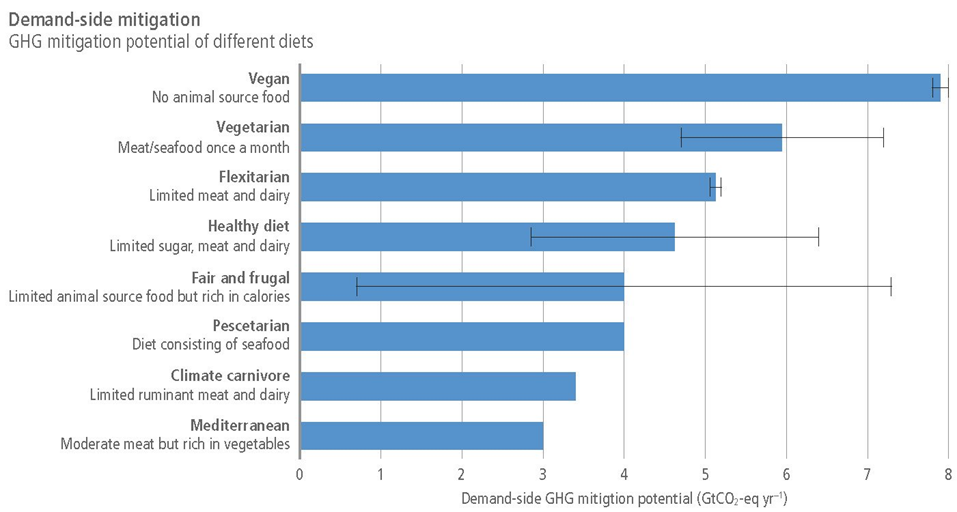

The 6th IPCC report published in 2022 includes in Chapter 5, Food Security, an assessment of Greenhouse gas emissions associated with different diets (5.4.6)(3): “...higher consumption of animal-based foods was associated with higher estimated environmental impacts, whereas increased consumption of plant-based foods was associated with estimated lower environmental impact. Assessment of individual foods within these broader categories showed that meat – sometimes specified as ruminant meat (mainly beef) – was consistently identified as the single food with the greatest impact on the environment, most often in terms of GHG emissions and/or land use per unit commodity.”

The following chart illustrates the GHG mitigation potential of different diets(4):

It is pretty clear that a WFPB diet is better for the planet. So what next? What does this mean for landscape architects in our region? Perhaps this is another opportunity for landscape architecture as a profession to take an important lead in reducing the pace of climate change, working through IFLA member associations providing some guidance or suggestions to local branches and their membership. Annual conferences, council or board meetings, local seminars or company events could all consider a change to WFPB catering at large and small functions, taking a practical and easy tangible step as part of a professional contribution to limiting the impacts from climate change.

Approaches to types of food production and patterns or preferences in food consumption vary widely across our region, but in each of our cultures there will be opportunities to reconsider the environmental costs of what we eat and move closer to a WFPB diet. For example, it was great to see a range of vegan cafes open in Jakarta last year, while I was chairing a panel reviewing the landscape programme at Institut Pertanian Bogor. My university hosts were delighted to sample an excellent range of delicious food in Jakarta; a small but important step that may spread to the whole of the Faculty!

Let’s all encourage the profession at a local, national or regional level to take the lead and embrace a simple but immediate and effective contribution to reducing the impacts of climate change.

image credit: author (Assoc. Prof. Mike Barthelmeh)

| Mike was a Fellow of the NZILA, later becoming the Institute’s delegate to IFLA, a role which he held for six years. He resigned from the delegate role and the NZILA in 2022 but has continued working in landscape education through his role as chair of the IFLA Asia-Pacific Region accreditation panel and chair of the Education, Recognition and Accreditation working group for the IFLA EAA standing committee. mikebiflaapr@gmail.com |

- Carlos A. Monteiro. “Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing.” Published online by Cambridge University Press: 1 May 2009

- Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/climate-issues/food

- Climate Change 2022. Mitigation of Climate Change; Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Retrieved from: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2019/11/Figure-5.12.jpg

(Further reading: an excellent research-based book on the health benefits of a WFPB diet is The China Study, by T. Colin Campbell and Thomas M. Campbell, first published in 2004 (ISBN: 1-932100-38-5). For a quick introduction to UPFs, see the NZ Consumer page https://www.consumer.org.nz/articles/ultra-processed-foods-are-they-the-latest-nutritional-baddie-on-the-block )