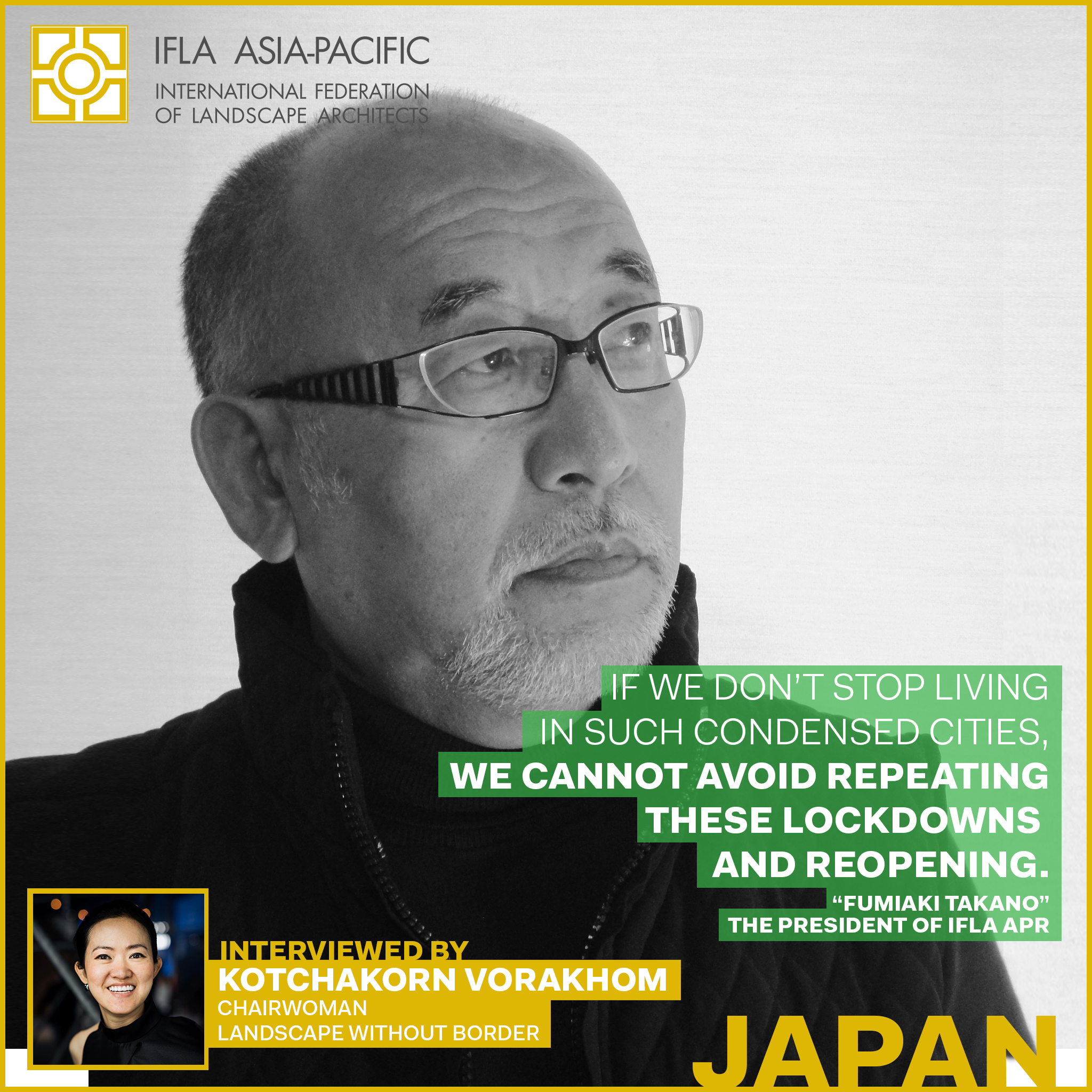

Conversation with IFLA APR President, Mr Fumiaki Takano

Kotchakorn: It’s so nice to have you with us today. Mr. Takano.

Takano: Hi Kotchakorn, we were planning to invite you to Japan in March to visit the natural disaster site of the tsunami in 2011, together with Professor Uehara. We wanted to have your lecture in Tokyo, and we were excited to have a meeting of landscape architects there. It is unfortunate we had to cancel that due to the pandemic.

But I’m very happy to see your strong leadership as the chairwoman of Landscape Architects Without Borders (LAWB.). As the President, I really appreciate that. About 10 years ago, right after the big earthquake in Chile, one female delegate [at a conference] shared with us about her country’s suffering. She addressed landscape architects and asked what IFLA could do to help. Her speech was quite shocking and sensational, leading us to a serious discussion that gave rise to LAWB. I think she would be very happy to see a person like you lead the young generation and carry her spirit onwards. I’m very happy to participate in this interview program.

K: This is such a beautiful story and I feel very honored. Thank you for sharing it with us.

T: It’s very important for each leader of IFLA APR’s committees to show strong leadership.

K: Mr. Takano, having 50 years of experience in the profession, I am sure you have been through the ups and downs of many global crises including this Coronavirus pandemic. What will be your prediction on how we as a profession will get through this?

T: I believe this has made us think more about the changes taking place from the bottom of the social structure. When Europe suffered from the Bubonic Plague, though a horrible event, it brought about the Renaissance—new culture, art, philosophies, and technologies. I’m sure that with this pandemic we’re facing now, we’ll have a chance to create positive changes for society.

For example, I think many people sought to live in big, dense cities with tall high-rises in an urban environment. At the same time, globalism has become very prominent as people busy themselves traveling around the world. These two concepts have become symbols of success for many business people, as well as landscape architects.

But when the pandemic began, those two symbols turned strongly against humans, causing us to suffer because our high urban densities and globalism spread the coronavirus all over the world. This pandemic raised fundamental doubts about the direction we were heading.

K: When speaking about social changes and the need for other possibilities, perhaps resilience in sustainable design to counter the damage we have done, how would you describe this positive change for landscape architects?

T: We have to think about urbanism. Many people still think of it as the concentration of people moving into big cities—this is what we need to reconsider.

K: What about urban sprawl, Mr. Takano?

T: I don’t mean to promote urban sprawl but a more equitable approach, a balanced distribution of development

K: The distribution of development shouldn’t be bundled up in one big chunk, but rather distributing these opportunities more evenly.

T: We should start by spreading out the population more, instead of just concentrating it. Though cities are growing large, rural areas still remain abundant in many countries. These two works together like wheels on a car—if they are not balanced, the car will not run straight.

But after several discussions during the pandemic, many are still focused on solving the issue within big cities. Instead, let’s consider how we can restructure our country—I think if we move more people into rural areas, there is more room for problem-solving.

People discuss a lot about social distancing, but with such a high urban destiny, it is almost impossible. I used to work in Tokyo for 15 years, but 30 years ago, I decided to move out to Hokkaido. We are now operating in an office in a very small farming village with a population of a few hundred people, but we still manage to do many international projects. It is not necessary to live in a big city.

In order to create a safe living environment away from coronavirus, we need more space and more nature. If we have that, we can have better design and more possibilities as a landscape architect.

K: I personally appreciate the rural and urban areas that you’ve shared as examples of open space for our practice. As landscape architects, what can we do to push forward the changes you speak about?

T: First, we need to go back and learn about our own culture. Globalism taught us about many new things happening around the world, but at the same time, its influence grew too strong and made design homogenous. People began losing their own cultural identity in design. More than just technical answers, we can find great solutions to coexist with nature in our own cultural background. When I was in Bangkok a few years ago for the IFLA conference, I asked my students to take me somewhere nice. They brought me to your design site at Chulalongkorn University Centenary Park. It was wonderful. I realized design, as modern as it can be now, its philosophical background is very deeply rooted in your culture—how Thai people relate to water and live with nature.

That is key to future design possibilities; people tend to forget the rich culture and philosophy in their own countries—we should start there. Now, the pandemic has disabled us from traveling a lot, so we have more time to study at home.

K: Thank you for your example. Even Thai designers forget that too, especially as our country becomes paved in concrete, we forget our natural landscape which is a core principle of design. What are other changes we can learn from this global pandemic?

T: We learned a lot of things from working remotely during the pandemic. We didn’t have to commute or go on business trips, saving more time and costs. Being at home, we have more time to see our family. We had the opportunity to see our own neighborhood and meet our neighbors. Now we have a better neighborhood network. All of this built lots of potential for future community design.

I think Thailand is working hard towards public participation, and I think this experience has presented a great opportunity to improve upon that. If we introduce more workshops and public participation in building parks and green infrastructure, I think it would be very helpful not only for the exchange of ideas but in motivating people to take initiative and responsibility in the usage and maintenance of these public spaces.

Workshops tend to just collect the voice of citizens making requests to the government, but I think that isn’t right. I think we should change the community design process to encourage people to work for their own community and neighborhood.

K: I think what you said is very relevant to our late king’s Self-Sufficiency Theory. King Rama 9 was very involved with ecology, and his concepts related a lot to self-contained communities as well as to Buddhism.

What about human connection in a broader sense? We had planned for an IFLA meeting in Malaysia this August, but now it cannot happen. What does this mean for our modes of communication and sense of community, during this time that we cannot be together?

T: We work in a profession that combats climate change, yet we get on airplanes that emit carbon. It’s funny that we come together to discuss global warming while we are contributing to it. But if we use online communication, we can avoid those environmental impacts. We are now considering how we can re-organize these conferences and our methods of communication. I miss face-to-face interaction, but we have to somehow compromise between the two.

K: We miss the human connection, but that, too, can be represented in various forms.

T: If we don’t do these online conversations like the one you’re organizing now, we actually talk less, maybe only once a year meeting face-to-face. But it has its advantages and disadvantages and we need to use both.

K: I admire your positive take on it. Cities are now reopening and it is highly likely that they’ll always have to impose lockdowns back-and-forth again as people come together again. How can we as landscape architects help aid that transition?

T: That’s a difficult question. If we don’t stop living in such condensed cities, we cannot avoid repeating these lockdowns and reopenings. Even now, I think this terrible situation may continue for a year and even more. We are rushing for a quick answer to this problem, but unless we fundamentally change from the basics, it will be very difficult.

K: During these lockdowns, people are becoming more stressed and longing to be in open spaces. With our profession dealing directly with places such as parks, gardens, and streetscapes, in your perspective, what new role do we have and what design aspects should we be more concerned about?

T: A few weeks ago, I had a conference in Malaysia with a similar topic. Many landscape architects were proposing many technical solutions, many of which were interesting, but I still think the most important thing still lies in the basics.

We need to change our city density. In big cities, the ratio of people to green spaces is unbalanced. We should question whether we’ll continue to create big confusing cities, or redesign our relationship with cities and rural areas.

If you look at big companies in Tokyo and Bangkok now, perhaps 30 percent will have to stay, but the rest 70 percent can operate in the countryside. This means 70 percent of their families will also move, reducing urban pressure and making it easier to make comfortable spaces and green infrastructure.

K: We’ve seen so much inequity in our societies during this lockdown, with the work-from-home culture as a real privilege for some professions and unavailable to many such as daily essential workers. How can we landscape architects promote more just and equitable societies?

T: Before, our skills and knowledge as landscape architects can help many situations. But now, we’re faced with much more complicated problems. Landscape architects alone can’t solve the problem—we need to work with politicians, economists, city planners, and sociologists all together.

We cannot leave people behind, as well as any country behind. Now we have 14 associations as members of the IFLA APR, but we have 18 more non-member countries in our region which I am trying to invite into the IFLA network. Many countries are developing, and they’ll really need a good landscape architectural point of view to build a good relationship with nature and the urban environment. Without landscape architecture, they might end up with another big city masterplan.

Since I’ve become the President, another idea I’ve proposed is an internship program. We have many Thai university students in the internship, which we’ve been doing for over 30 years with over 300 students from 33 countries across the world. Even our small office in Hokkaido can do this. If each of our IFLA APR members in the 14 associations, perhaps three offices each, started doing this and networking with each other, I think it will create lots of opportunities for the younger generation. I think it’s very important to work in a foreign country and work with students from other countries to exchange their knowledge and philosophies to build strong fundamentals for the future of landscape architecture.

K: This is a really strong insight on how we need a multidisciplinary working approach in order to create a truly just world, that we cannot work alone. With that, we need to share these opportunities with many countries, as well as for the younger generation to learn these differences in working abroad. I think creating a just world is about understanding our differences to figure out a place where we can live together.

T: Before, many people would go study abroad—I went to the US, and you too—and come back and start building their own concepts and philosophies, mixing together their overseas experience with their own culture.

Saying that, many students in Japan want to work with you. We are now at a stage when we’re learning more about each other within Asia, not just across the continent, and it’s important to build upon Asian landscape identities—each country is not the same, whether with their nature or culture.

K: So what is your message to the world and to landscape architects right now?

T: We are heading to a different stage of our profession. We’ve discussed previously within IFLA about how can we can upgrade the professional position within each country, but now we need to face much bigger problems like climate change and the pandemic and its impacts on the future. And to work on that, I think we need a stronger network within Asia and much more experience working together. I’m hoping the internship program could be the base of this idea. If this could be integrated with the educational curriculum, perhaps a student could spend a half-year in Thailand or in Japan, and these experiences could be credited.

K: There are connected problems of climate change and this pandemic. What is your thought on this?

T: When speaking about climate change, many people say it’s important, but many also say it’s difficult. But during this pandemic, we had to stop many things like factories and transportation, and so even in one or two months' time, air pollution and CO2 reduced. So if we wanted to do it seriously, I think it’s possible.

Now people in India can enjoy the fantastic view of the Himalayas and the water has become cleaner in Venice, and even the beaches in Thailand. So if we really want to change, I think we can. The pandemic showed some of those examples, and it’s been very encouraging to me.

K: In such a dark period, we still saw a light of hope.

T: But we had to change from the basics. If we wear a shirt and misplace the first button, then we get the rest all wrong and we’d have to go back and change from the beginning. Cities are similar. When discussing how we can solve the pandemic issue, we can’t just think about the surface. We have to dig to the bottom of philosophies and of people.

K: Many professions, such as in healthcare and business, have been shaken and changed. But I feel like our profession has stood very strongly with our direction in creating a better world and environment and we’ve just had to align our work with the circumstances of the current challenge. What are your thoughts on that?

T: I think you’re completely right. I’m not pessimistic about it, and I’m sure landscape architecture has a bright future if we work cleverly. I’d like to propose for landscape architecture firms to move out of cities to spread manpower. Perhaps have a headquarter in the city, but production can be done in rural areas too. It would create lots of interesting activity which can reduce pressure in urban areas, where we would have more space to improve the situation too. Also with new people coming into rural areas, we can activate these villages. These are interesting things I’d like to see happen.

K: When you speak about distributing manpower, are you also suggesting that we not only focus on designing big cities but for landscape architecture to serve the natural world, biodiversity, and communities in developed rural areas?

T: We need to do both together. It is very difficult to try and figure out social distancing when we are living so densely in a concentrated city, and we’d only be coming up with surface solutions.

K: Thank you so much. Mr. Takano for your shared visions. After this, let us share with you views from another 14 landscape architects across the Asia – Pacific region about their vision, hopes and fears and what we, landscape architects, can contribute to the reimagining and reshaping the world after this pandemic.

*Please join us in shaping our post-pandemic world and landscape architecture profession, by sharing your thoughts and idea aspirations for the new world you envision. We will be collecting everyone's ideas and sharing them with our Landscape Without Borders Community. It is time, we look forward to hearing from you. https://forms.gle/PEP8nFia17WBAkvK7

Produced by: IFLA APR Landscape without Border, Kotchakorn Voraakhom, TALA, and IFLA Secretary team

Text editor: Assoc. Prof. Mike Barthelmeh NZILA

Graphic: IFLA APR Landscape without Border, Watcharapon Nimwatanagul, TALA

Communication: Bosco, So Ho Lung, HKILA