Transitional Housing: An Australian Perspective

Q1. The need for transitional housing in your country

In Australia, the single biggest cause of homelessness is domestic violence. Poverty, unemployment, a shortage of available dwellings and affordable housing options, and inadequate rent assistance and other social security benefits – also create demand for transitional housing. Family breakdown, mental illness, domestic violence, addiction, financial difficulty, gambling, and social isolation can also play a role in homelessness.

Last year, Australia’s state governments were concerned that people sleeping on the streets were extremely vulnerable to contracting Covid-19 and posed a public health risk to the wider community. So, during the first six months of the pandemic, they provided transitional housing (mainly in empty hotels) to more than 40,000 people. But a year on, only one-third of those people have been moved into more stable housing, with many instead returning to the streets or to homeless shelters.

Most Australian homeless people have experienced extreme weather including severe storms (including hail, electrical, dust or flash flooding), extreme heat and cold, bushfire cyclones and flooding. Climate change presents a serious risk to the Australian environment, economy, and communities; and will inevitably increase the need for transitional housing.

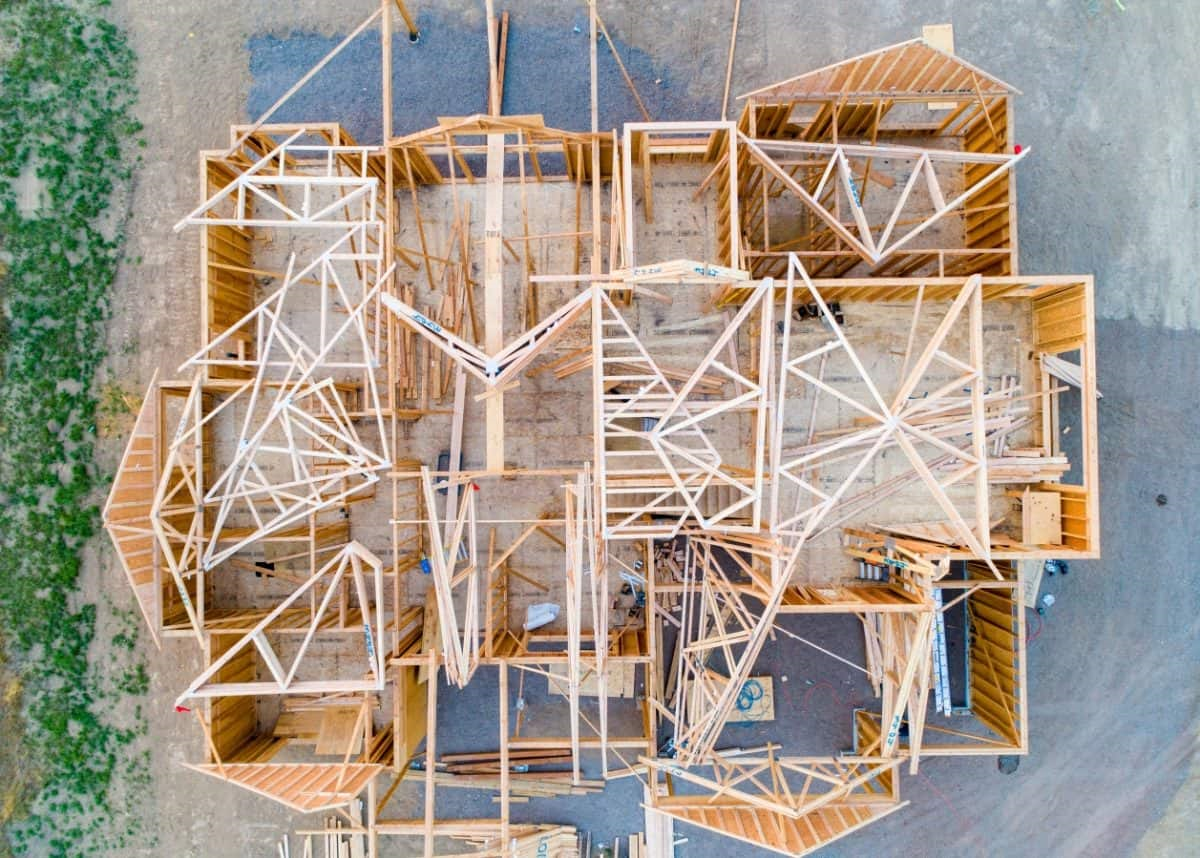

Q2. The development of transitional housing in your hometown.

I live and work in Melbourne in the state of Victoria where it is estimated an extra 166,000 social units will be needed by 2036, with around 44,000 households on the social housing waitlist. The Victorian government recently announced the A$5.4 billion “Big Housing Build” which aims to create over 12,000 homes in four years. Of these, 9,300 will be social housing, while the rest will be affordable or market-rate housing, with landscape architects involved in all the large-scale “fast start” new build projects.

Q3. How does transitional housing tackle climate change or other social problems?

Landscape architects can help governments to develop strategies for transitional housing, existing buildings, and longer-term affordable housing, through land-use planning assessments and controls; by inputting into the National Construction Code and standards; by helping to locate buildings in less hazard-prone areas; and by designing green infrastructure that mitigates Urban Heat Island Effect, and reduces the risks associated with heat, fire, and flood.

In Australia extreme heat leads to more fatalities than all other natural hazards combined. The City of Melbourne has an extreme weather program, designed to provide relief for people experiencing homelessness or disadvantage. Cooling centres have been developed as places where people without adequate shelter can find respite in extreme conditions and landscape architects are increasingly designing heat refuges into new public parks as part of the extreme weather program.

Q4. Are there any landscape interventions or mitigation measures applied in some of the transitional housing schemes? The temporary housing for the bushfire crisis in Australia/ 311 Tohoku earthquake and Tsunami in Japan, temporary shelters, and other areas in flood-hit Thailand, etc.

In 2020 more than 3,000 houses were destroyed in the 24 million hectares burned, leaving many people temporarily unhoused. In New South Wales and Victoria, modular self-contained transitional housing pods were supplied. Equipped with a 2,300-litre water tank and 5 KVA generator, they aimed to get people back on their land and into their communities while they rebuilt.

Virtual platforms were also deployed to help to provide transitional housing; including emergency accommodation and rental housing assistance, as well as online booking of open homes, spare caravans and vacant holiday houses. The virtual platform Architects Assist, was established as an initiative of the Australian Institute of Architects, supported by the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects and the Planning Institute of Australia, with over 600 firms from the built environment industry offering to work pro-bono to help support those affected by natural disasters and other adverse circumstances. The platform directs members of the community to one or more of the volunteer practices. The practice then assesses their enquiry and explains the options to them. Depending on their circumstances, the extent of pro-bono assistance may vary from simple advice to full service.

Landscape architects also provide guidance in relation to building on bushfire-prone land through siting, planning and design. Primary considerations include understanding the environmental constraints, how best to site the building, low risk landscape solutions, ease of maintenance, local emergency management arrangements, active defence solutions, and on-site refuge options; as well as vegetation, landscape features, ignition sources, slope, aspect, and access must also all be considered, as well as the lot’s location and position within the lot, minimisation of vegetation (through low density non-continuous vegetation, and species/type that don’t burn readily), effective distances between the vegetation and the building, and the design of the building and surrounding landscapes allowing occupants to conduct regular maintenance checks, and to maintain gutters, lawns, gardens and trees.

Q5. Are most of the transitional housing developments subsidized by the local government or NGO? Did the community find a chance to recover through these programs? What leads to the Transitional housing scheme being successful in your country?

One of the most enduring models of transitional housing in Australia is the quarantine station. There are historic examples located right across Australia built from the 18th century onwards. They typically comprise of small, single story buildings with good cross ventilation and plenty of outdoor space.

In the Northern Territory, a former mine camp, Howard Springs (named by Traditional Owners Larrakia Stringybark signifying shelter), is now being used as a pandemic quarantine centre referred to as The Centre of National Resilience. It was built in 2012 and designed to attract and retain and hold 3,500 resource (mine) workers and cost A$600M to build. Featuring award winning urban design the camp was masterplanned around a series of tropical courtyard buildings, with green spaces and corridors, landscape zones, native pants and based on sustainable principles.

The Victorian State Government has recently announced plans to open another COVID-19 quarantine facility, narrowing down from ten possible sites to, one north of Melbourne and to the west near Geelong. It will be a purpose built 500 bed facility with capacity to extend to up to 3,000 beds. The detailed design is costing $15M with construction costs estimated to be A$200M. The quarantine station will be funded by the Commonwealth Government and operated by the State Government. The construction will take four months and it is hoped it will be operational by December 2021. Accommodation comprises bespoke, standalone relocatable units for singles, couples, and families.

The new Victorian quarantine station will need to be planned around clear separation, with independent verandas set further apart, without any communal areas and could be designed to produce more than it consumes in terms of power and water. There are perhaps three possible models for the use of the quarantine station after the Covid-19 pandemic:

- The first option is to leave it in place for use future if/when there are other pandemics, or when communities need to be relocated because of natural/climate change related disasters like fire, storms, heat, and floods.

- The second option is to retain in place in and re-purpose from a place where people are separated from the community, to one where the community is brought together. This would entail community engagement and a community needs assessment and the re-planning and design of new communal spaces which could be facilitated by landscape architects. The station could be used for youth/school/sports/summer camps, or for local arts/cultural or educational programming.

- The third option is for the units to be relocated into communities across Victoria, as standalone independent living units or small villages for short or long-term transitional housing. The could be re-designed around a sense of neighbourliness, stitched together with communal walkable spaces, an linking internal and external spaces.

Transitional housing in Australia is subsidised by a combination of state government, local government, and NGOs. Some of the transitional housing strategies included rapid easing of planning controls, allowing people to stay in caravan parks or camping grounds, installing a movable dwelling on their land for up to two years without requiring council approval, as well as making large public spaces available as basic camping grounds or emergency evacuation centres. Other strategies included the deployment of tiny homes across the country into the private rental market, as independent living units providing short and long-term transitional temporary housing, or emergency shelter and post-disaster relief.

Tiny Homes projects/pilots typically include small units with a bathroom, kitchen, sleeping area, living area, a small deck and rainwater tank. Some include common laundries, lounges, and vegetable gardens. They were deployed in bush fire impacted areas, as well as in the New South Wales’ Central Coast, Melbourne’s inner west, and through suggested networks of tiny house villages in the Gippsland region. Prefab21, a prototype that utilises new prefabrication technologies, was developed by FormFlow, Samaritan House Geelong and academics and students at Deakin University’s School of Architecture and Built Environment and provides six-star energy rated accommodation with a reduced carbon footprint (because all components could be recycled) including passive solar features.

Q6. Any idea of incorporating the landscape architecture design in the existing transitional housing? (For example, some movable landscape included vegetation/ tree/ library/ Festival/ Flea market transformable stage for the temporary housing.)

Transitional housing sites will still be required as a stepping-stone because of the time required to implement permanent housing solutions and the increased likelihood of more natural disasters and climate emergencies; creating opportunities for landscape architects to be more involved - by identifying sites for housing networks and helping to conceptualise ideas for public engagement.

Landscape architects, in advocacy roles across Australia, are informing planning and legislation changes that seek to increase the supply of affordable housing through incentives and mandated targets. They also help to ensure the success of these planning approaches, for both short and long-term housing needs - by bringing people together, showing government, developers and the community what is possible, testing out ideas, and inspiring long-term change.

Landscape architects can also further address the growing housing crisis through multi-disciplinary collaboration; enhancing the resilience of communities, by integrating temporary housing interventions into urban landscapes through good design and co-design, by including community integration, though walkable and safe streets, by linking internal and external spaces to support flexibility, by combing public, private and communal landscapes, and through the role of the garden and value of horticultural therapy.